Adapting a classic with a classic reputation is always tricky. Almost as tricky as a director with a settled style stretching himself into new directions. Both are treacherous, filled with pitfalls and observers eager to point out how the earlier stuff was better.

And there’s a lot of risk, too, because there’s a lot of failure. Attacking a film that no less than Alfred Hitchcock made his American reputation on might not seem like the best thing to start experimenting with style. On the other hand, when you start where Ben Wheatley has, what better time is there than now?

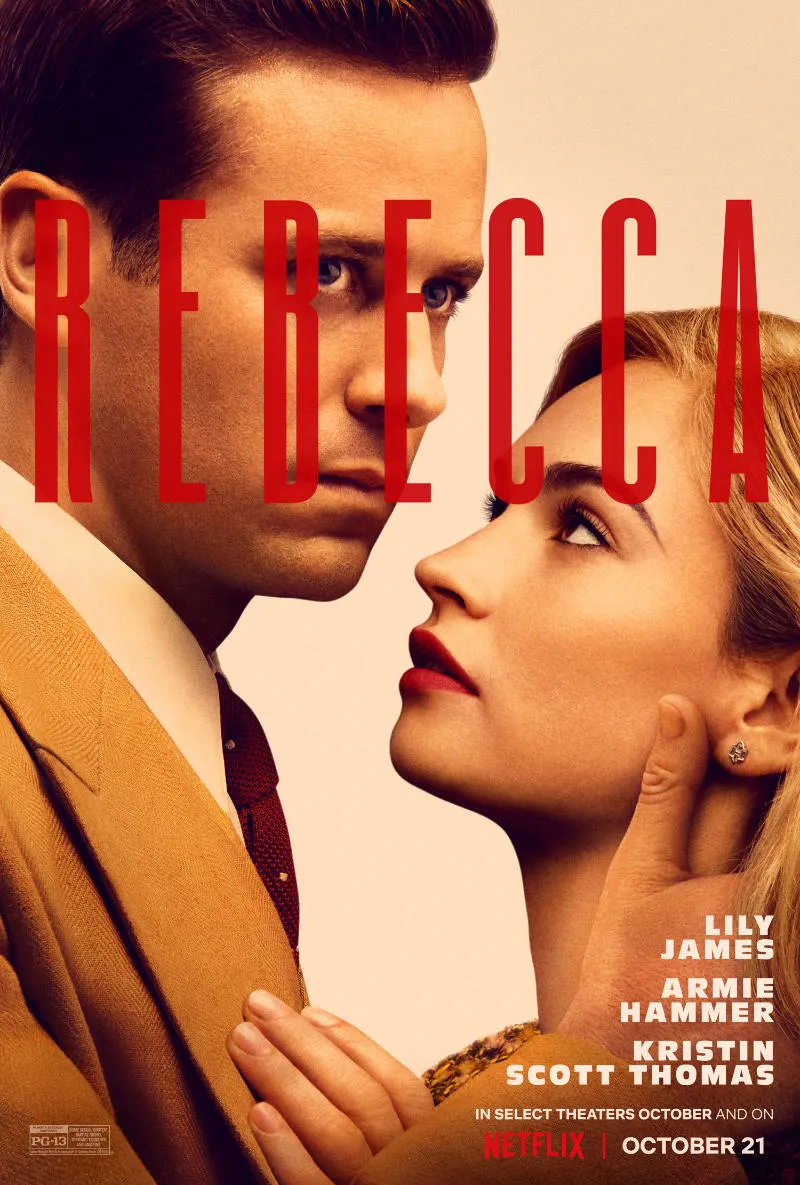

Rebecca itself is a classic psychological drama, so much so it’s surprising it has not been returned since Hitchcock’s Best Picture-winning adaptation. Taking a lot of inspiration from Jane Eyre, Rebecca follows the sudden meeting and marriage of Maxim de Winter (Armie Hammer) and his newest wife (Lily James), who quickly discovers that she is in over her head.

Feuding with the controlling, passive-aggressive housekeeper (Kristin Scott Thomas) and trying to find a place for herself in a world she’s never been a part of, the newest Mrs. de Winter finds herself dragged into accusations of betrayal and worse, and always struggling under the memory of the long-dead Rebecca.

Wheatley has long been a director of psychological torments where what might be happening is so much more engaging than a simple ghost or other horror staple. He is a director of films that suggest what might be happening, except he’s never bothered with suggestions.

Mixing dead-pan humor and bizarre color patterns, Wheatley has pulled the character’s interior world out for plain view. On the surface, a period drama of understated psychological torture would not seem to play to his strengths as a filmmaker.

And yet he plays it straight most of the time. It’s impossible to think that anyone making this version of Rebecca was unaware of the shadow cast by Hitchcock’s version, but at no point does it appear to be a replication or even wink and nod at the older sibling.

It’s much more focused on the relationships between Mrs. de Winter and her husband and rival, trying to keep the audience as much in James’ head as possible.

The impossibility of truly knowing anyone is Rebecca‘s core issue, and James is the unfortunate Sisyphus who keeps throwing herself at the problem. Being naturally withdrawn and unsure of her surroundings, Mrs. de Winter isn’t the kind of giant personality to keep the film’s world revolving around her. Events happen to her, not because of her, generating a passivity that is difficult to fully engage with. Jane Eyre would have sneered at her.

It’s always been Mrs. Danvers who excited the imagination and Thomas excels in the role of barely sustained sanity, a physical manifestation of Rebecca de Winter’s ghost. She commands each scene even when doing nothing; it’s no wonder James, the ostensible lead, seems to fall into the background around her.

Perhaps that’s impossible to avoid, it’s basically the same dynamic as the book. Perhaps some of Wheatley’s visual adventurism could have added more personality to the flatter characters, intimating in look at what is left less than suggested in words.

There are a few moments of the old Wheatley in there. His costumed ball avoids red like the plague to further point up James’ singular disastrous look when she is tricked into wearing one of Rebecca’s old dresses. A nighttime stroll under fireworks of conflicting red and blue, where colors fly into one another like battling thunderclouds, visually representing James’ increasing turmoil.

But then it all calms down back into more staid patterns. [It reminds strongly of similar decisions Justin Kurzel made earlier this year for True History of Ned Kelly Gang]. Rebecca is polished, poised, period perfection made with care and exactitude with performers giving exactly what the script calls for. But it’s never more.

The hint of madness lurking just underneath seems like a perfect visual recitation of the film’s themes, but really, it’s a suggestion of what Rebecca could have been. In some ways, it is Ben Wheatley’s strangest film as it is so different from what he’s done before. But this time, that wasn’t the right decision.

Rebecca Review Score: 7.5/10

Rebecca will be available on Netflix starting on October 21, 2020. The cast also includes Keeley Hawes, Sam Riley, Ann Dowd, Tom Goodman-Hill, John Hollingworth, Mark Lewis Jones, and Bill Paterson.

Joshua Starnes has been writing about film and the entertainment industry since 2004 and served as the President of the Houston Film Critics Society from 2012 to 2019. In 2015, he became a co-owner/publisher of Red 5 Comics and, in 2018, wrote the series “Kulipari: Dreamwalker” for Netflix. In between, he continues his lifelong quest to find THE perfect tomato soup and grilled cheese sandwich combination.