Aaron Sorkin is a writer’s writer. That doesn’t mean he routinely writes excellent dialogue (though he often does) or complexly crafted characters (though he sometimes does) or even that his work is accoladed or influential to other writers (though some of it is). It means he does what all writers do, only more so.

Sorkin has a story to tell and characters to tell it with, but ultimately, all he has is himself, and whatever comes out of his pen will be some facet of himself. It’s no accident that many of his characters have the same interests and habits as their creator or chronicler or deal with the same conflicts and stumbling blocks.

Sorkin is not unique in that respect, all writer’s pull from themselves because they have to, he’s just one of the most upfront about it. In that sense, there is no Chicago 7; there is only the Chicago 1, and that one is Sorkin himself.

Except there also was a Chicago 7 (originally the Chicago 8). In the humid summer of 1968, multiple protest groups descended on the Democratic National Convention, where they tangled with police in violent, wide-scale riots. The Nixon Administration placed eight of the group organizers on trial in a physical manifestation of the counterculture movement versus the establishment.

The trial was notable for the binding and gagging of defendant Bobby Seale (who was eventually severed from the trial), the participation of many celebrity witnesses, and a general feeling of being a media circus. For the people in the trial, however, it was nothing less than a fight over the soul of America.

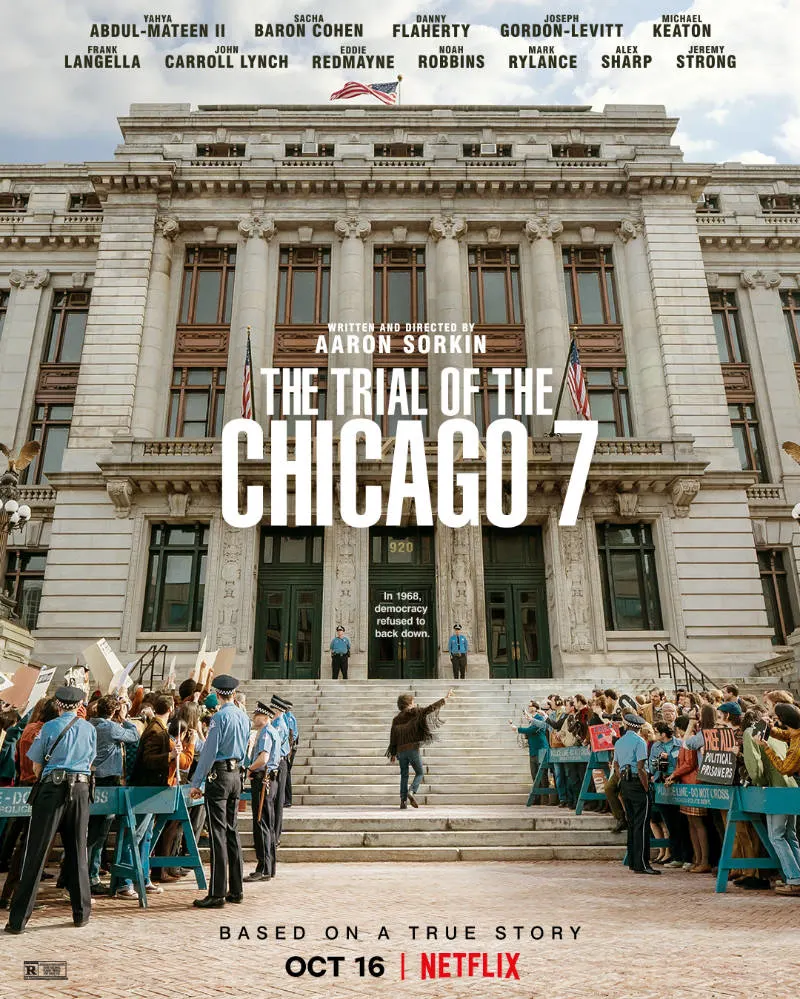

The Trial of the Chicago 7 is the ultimate Sorkin film, filled with intelligent, over-the-top characters battling within a civil structure over the ideals of America. It is filled with every trope of a Sorkin film. It provides options for playing with timelines, playing with location, and monologues about patriotism and society’s responsibility to itself.

More than its content, the movie’s very construction is the epitome of the Sorkin playbook. Any idea a character rants against, he is ultimately revealed to be guilty of. Any action a character protests should never be done; he will ultimately perform himself. None of this is bad. In fact, it’s what makes his work so good. Because Aaron Sorkin is a writer’s writer.

The proof is in the performances themselves. Great actors can get good performances out of almost anything. But most of what we think of as great performances are built off of great roles. Sorkin routinely, almost effortlessly, gives his actors great roles to play with and marvelous dialogue to deliver.

The Trial of the Chicago 7 is no different, creating — just as with his work on The Social Network and Steve Jobs — amalgamations of real people and sending them through the Sorkin lens to amplify their best and worst attributes. Eddie Redmayne and Sacha Baron Cohen get the meatiest work as the proponents of protest and activism but are also frequently upstaged by the befuddled intellectualism of Jeremy Strong‘s Jerry Rubin (channeling Tommy Chong as a civil rights lawyer) and the quiet of anguish of Yahya Abdul-Mateen II‘s Bobby Seale.

The negatives of a Sorkin work are also unavoidable and also on display. Though in his second directorial effort, his sense of visual storytelling continues to increase, everything is ultimately slave not just to the words (which is a fair trade-off) but to the perquisites of his initial home: the theater.

After a brief introduction, almost all action is left to the courtroom, itself standing in for the stage where characters can pace and yell and declaim, but little can be shown. The inciting incident of the trial and the riots surrounding the convention are described or mentioned but left off-camera as long as possible.

This makes sense for a stage play, and on film, it creates the constant feeling of a stage play with action constrained on all sides, hinting at a world beyond the walls of the stage.

Except this is a film, and there is a world beyond those walls, one which can be shown. The nature of film is that it is a visual medium. ‘Show, don’t tell’ is the oldest rule in the game because it’s what we see that sticks with us. The Chicago 7 understood that better than anyone, hence the frequent displays of irreverence and provocation inside and outside of the courtroom.

Jerry Rubin himself explained as much as in The Sixties Papers: “[It] is a non-verbal instrument! The way to understand [it] is to shut off the sound… The picture is the story.” No Sorkin script or film will be like that; he tells more than he shows because he’s great at telling, and it shows. Then again, if any of the above were different, The Trial of the Chicago 7 wouldn’t be a Sorkin film anymore. As trade-offs go, it’s worth it.

The Trial of the Chicago 7 Review Score: 8.5/10

The Trial of the Chicago 7 will be available on Netflix starting on October 16, 2020.

Joshua Starnes has been writing about film and the entertainment industry since 2004 and served as the President of the Houston Film Critics Society from 2012 to 2019. In 2015, he became a co-owner/publisher of Red 5 Comics and, in 2018, wrote the series “Kulipari: Dreamwalker” for Netflix. In between, he continues his lifelong quest to find THE perfect tomato soup and grilled cheese sandwich combination.