Kingdom of the Planet of the Apes Review

The original Planet of the Apes was classic ’60s science fiction in the sense that it was focused on its central theme of man’s misuse of the planet and how easily nature could turn against us, but not necessarily on interesting plot or dialogue to carry its ideas to far beyond its natural borders. It was too in love with its own metaphor for that.

The recent returns to the story, focused on the years between the collapse of human society and the rise of the ape society that replaced it, have traveled in the opposite direction, offering only surface-level attention to those themes to support more complex character-based conflicts—a choice that has made them both more and less like their forebears.

Kingdom of the Planet of the Apes continues down that same path, offering complex newcomers in a fully realized world but little in the way of real development beyond the promise of tomorrow. Picking up several generations after the time of the ape liberator Caesar, his descendants have grown and scattered into a variety of different social groups grappling with the beginnings of society.

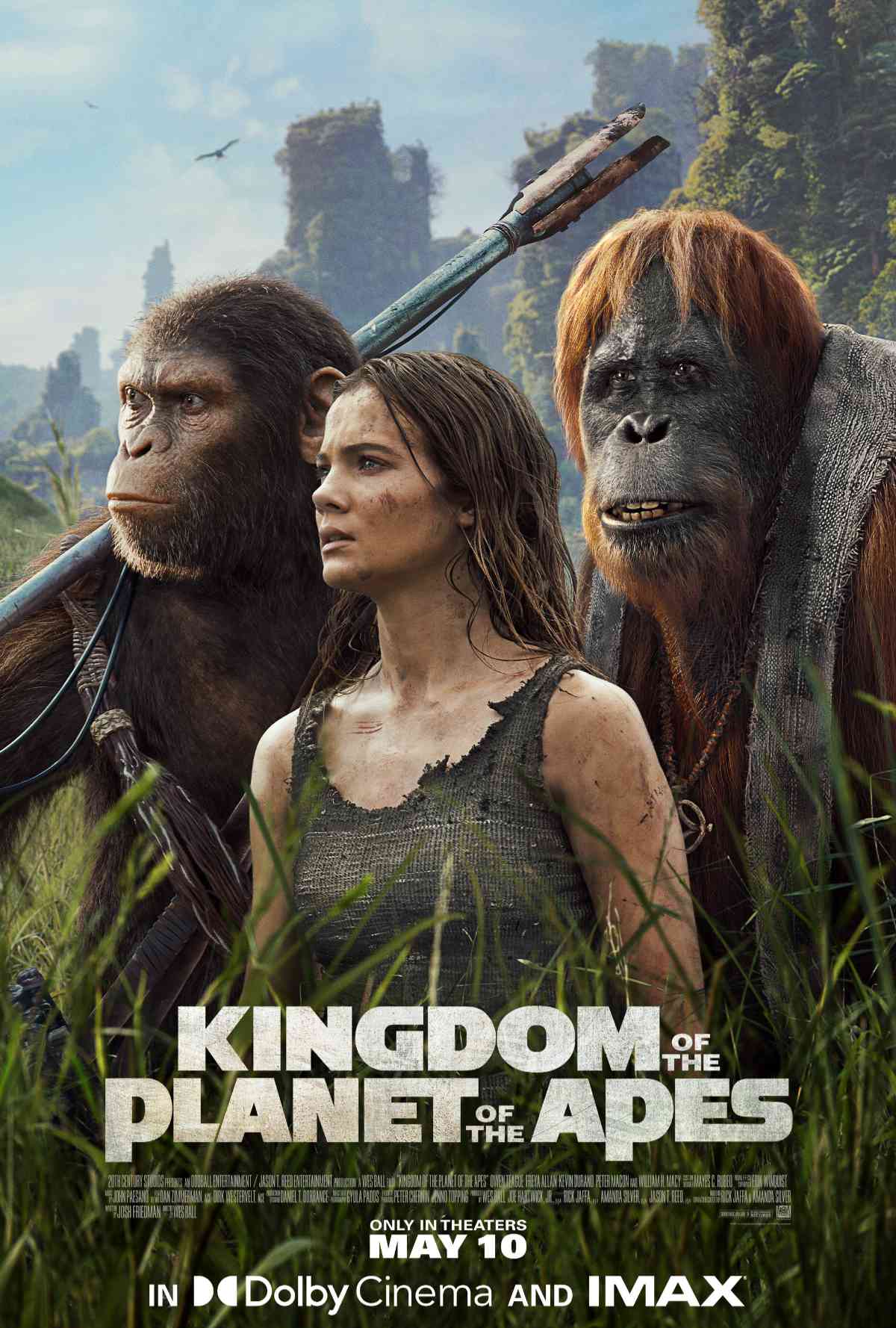

One such is the Eagle clan of Noa (Owen Teague), hunter-gathering chimpanzees who hunt with the aid of trained birds and know little of the world outside their valley. That complacency swiftly and violently ends when Noa discovers a human girl (Freya Allan), now a rarity in an increasingly ape-dominated world, and unknowingly brings a band of savage gorilla raiders down on his people.

Vowing revenge and the salvation of his surviving clan, Noa heads out into the wild undergrowth of downtown Los Angeles, discovering the wide world his elders had kept from him and that not everything about it was what he had thought … east of all his new human companion.

The promise of the modern Apes series since Matt Reeves took it over in 2014 has been the gradual unraveling of human society and the creation of the new world in its place, but so far, no one has had a real idea of what that means. Bands of apes try to find a place to live away from the humans who both made and cursed them but keep getting drawn into fights with them for domination of the world. Stir and repeat.

It has worked as well as it has because of the depth of its characters, particularly Andy Serkis‘ Caesar, and thirst for complex inter-character conflict, but the background keeps getting repeated. Kingdom of the Planet of the Apes at first seems to be heading in new directions as the Apes turn their backs on romanticized agrarian paradises and, with no humans to fight, begin warring on one another using Ceasar’s name to bless their deeds.

Before we know it, though, Nova reveals she can talk and is part of a remaining human society. They need something from the hidden nuclear vault that Noa’s foe, Proximus (Kevin Durand), is trying to access because “they’re not meant for apes.” The details are a little different, but the essential question of the last four films remains the same and essentially undeveloped: can man and ape share the planet?

Just as with the last few films, Kingdom gets away with the underwhelming themes by covering them up with a rich tapestry of characters well performed. Noa himself is fairly straightforward forward, but his slow reactions to seeing a new world (including a particularly heavy metaphor about a telescope) feel real, as does his growth into a leader of principle and strength.

He’s just outmatched by the world around him. Shortly after arriving in Los Angeles, he falls into the home of Raka (Peter Macon), an orangutan philosophy trying to spread the true word of Caesar and with the first truly unique view of the world of the Apes since the series was restarted. When he is not stealing each scene he is in, Durand’s Proximus is.

A truly magnificent bastard who knows what he wants and is understandable (if not agreeable) in his desires, he has taken on the worst habits of mankind—partly through the study of human history—ignoring peaceful farming for urban decay and tyranny.

There has long been a strain of know-nothingism in modern studio writing, looking upon cities and knowledge as fountains of decay and destruction, and Kingdom perpetuates that as much as any modern blockbuster.

It’s also painted upon a living, breathing canvas that feels real without ever trying. Noa and his band just happen upon a herd of zebras with no context for what they are but with all the rationale of where they came from completely clear. Every piece feels thought out and alive in a way films of this magnitude often try and fail at.

That’s also by design, as Kingdom spends as much time planning for what it wants to do in the future as it does telling the story of now, which makes some of its plate spinning only more obvious. ‘Wait,’ it says, ‘the best is still yet to come.’ Well, at some point, tomorrow must become today, and that point is fast approaching.

KINGDOM OF THE PLANET OF THE APES RATING: 7 OUT OF 10

Directed by Wes Ball, Kingdom of the Planet of the Apes is rated PG-13 for intense sequences of sci-fi violence/action.