Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull – A Look Back

With this Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull feature, we’re taking a look back at Lucasfilm’s other giant franchise and the ways it shaped the modern blockbuster. Stay tuned for all the latest Indiana Jones 5 news here.

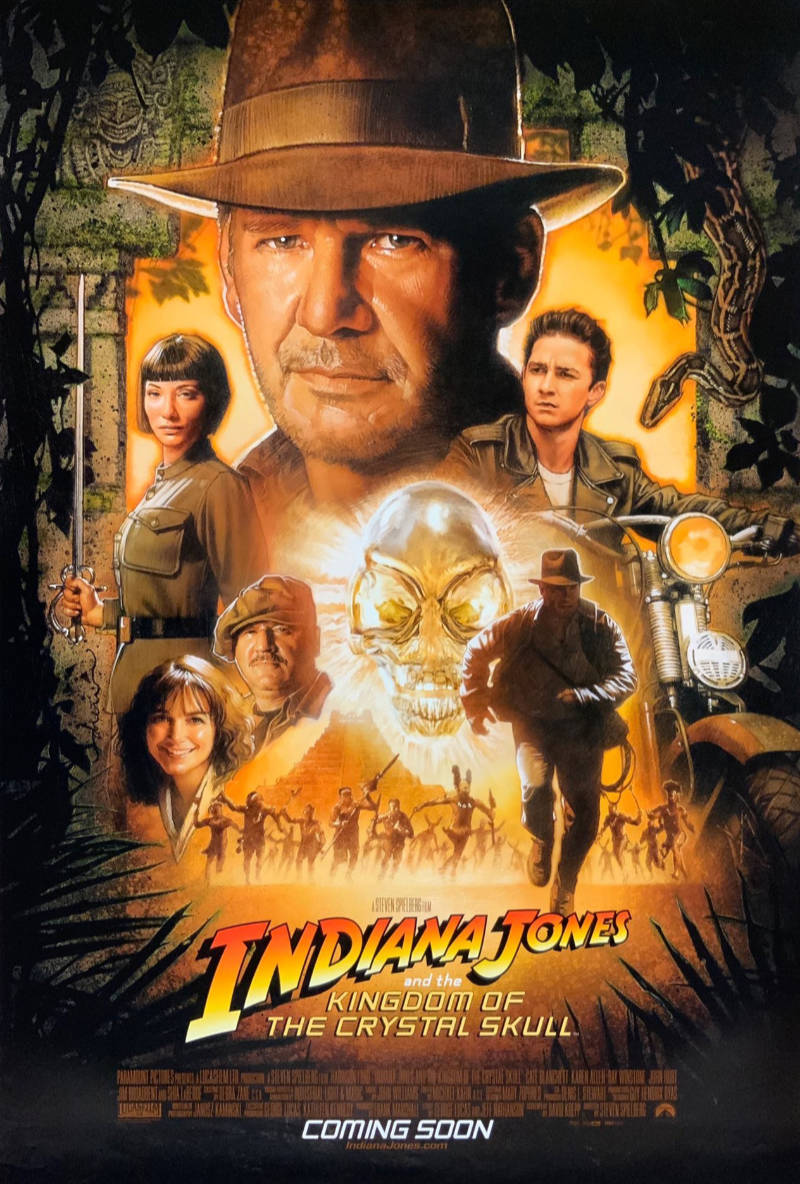

INDIANA JONES AND THE KINGDOM OF THE CRYSTAL SKULL

The first decade of Indiana Jones was a mixed bag of offerings featuring series highs and lows, neither of which would ever be really approached again. (At least so far). The burst of inspiration and melding of creative energies that created one of the great blockbusters spent the rest of the decade trying to recapture that former glory and always ending up somewhere (even when it tried retracing its own footsteps). The next decade was left in silence with all parties focusing their energy elsewhere.

And then, suddenly, Indiana Jones was back.

Suddenly actually means more than a decade of development as the diverging visions of what Indiana Jones should be, which had plagued the other two sequels, became more prominent. For all the delay, however, Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull (check price at Amazon) seems prescient, prefiguring a coming decade of studios returning to old properties rather than creating new ones.

That doesn’t have much to do with what makes Crystal Skull what it is (and isn’t), but the causes behind both are similar. After decades of silence and disagreement, Indiana Jones the character and Indiana Jones the series found themselves back at the same place they had been after Raiders of the Lost Ark – trying to figure out where to go.

Considering how intentionally regressive Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade was, this could be seen as completely fitting. More importantly, faced with the same problem that had cropped up in 1982 after a wildly successful launch, the Indiana Jones brain trust embarked on a similar path.

If Last Crusade practically begs to be viewed alongside Raiders, then Crystal Skull is only best understood compared with Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom.

Temple of Doom, which most grappled with the idea of who Indiana Jones is and why and what he should be, while its brethren focused more on where he came from without asking any questions it meant for his future. Nor was that something Last Crusade was going to bother with or thought there was any chance of, as it literally sent its hero off into the sunset.

Coming back to the franchise again the question became ‘would it look to the future’ as Temple of Doom did or would it remain fixated on the past? The answer is a bit of both. The sheer passage of time, nearly 20 years, meant the ability to replicate early facts outright as Last Crusade did was no longer possible.

New environments, new milieus, and new foes would have to be approached again, and Crystal Skull tries, sometimes haltingly and sometimes with a breathtaking exuberance. The results were divisive, largely due to the introduction of elements foreign to the series, which makes them the most important part of the film.

Old ruins and mystical elements are replaced with rocket sleds, psychic powers, and aliens. More importantly Indiana himself, now manifestly old (though played as more middle age), contends with not just the past as an idea but his past. Many of the individuals he spent his life with have died, and his place in society has suddenly become disposable with little tangible to show for it. Even his apartment is largely the same as it was four movies and 20 years prior.

And it’s all played against an increasingly futuristic (relative to Indiana, at least) background. Jet fighters scream through the air, alien spaceships open interdimensional portals, and in some of the film’s most iconic imagery, Indiana observes the aftermath of a nuclear explosion complete with a signature mushroom cloud. It’s a stark comparison to the explosive destruction of the Nazis by the Ark of the Covenant at the end of Raiders.

That awe-inspiring power has been captured by mankind, for better or worse, and its mystery has been revealed. It’s not an accident this happens near the warehouse where it turns out the Ark was left at the end of the first film, inside Area 51, exposing that secret as well.

All questions, Crystal Skull suggests, will eventually be answered by the passage of time — pried to the surface by some musty archeologist — whether we like the answers or not.

It’s moribund in a way none of the previous Jones films were, with almost every frame filled with evidence of time moving inexorably onwards.

In that sense, the film itself is a reflection of its central character. Many of the behind-the-scenes technicians have moved on or passed away just as Indiana’s friends and family have, leaving new hands to come in and decide whether to ape the work that came before them or create something new.

Both the production design crew and the cameraman for the first three films have been replaced with Spielberg’s 21st-century collaborators, which creates a frequently modern feel.

And it shows, not in a pejorative manner, but it is definitely different. It tries very hard not to be; everyone is working to match the look and feel of the older films, but the reality is time has moved on. It’s most noticeable in the camera work by Janusz Kaminski, which tries to mimic the slower work of Douglas Slocombe and its deep focus sensibility.

But the reality is Kaminski is not the same type of photographer, frequently bouncing light off various surfaces and playing with its characteristics, and has a lot more freedom of camera movement thanks to the advances in visual effects. The camera can now follow Indiana as he jumps off a motorcycle, climbs through a car window, and out the other side onto the same motorcycle.

Not that the film is all modern all the time. In fact, as much as Last Crusade did, it tries to maintain a specific, familiar aesthetic and remind us that ‘this is an Indiana Jones’ film, which results in Crystal Skull never developing its own distinct visual language.

Just as with Jones himself, the passage of time is impossible to ignore even as the film tries to make itself look as much like its predecessors as possible, including limiting the palette to different shades of greens and browns.

The weight of history denies Crystal Skull its own identity. In that sense, it does fit in with the film itself, which never seems to be sure what it is about either – is it a catechism about deciding what is truly important in life or a meditation on age and the nature of change?

The answer would seem to be ‘both’ but not in an organic sense, with multiple themes complementing and enhancing one another. It’s more like a fight with the need to create something new warring against the desire to return to something comfortable. The results were divisive, largely due to the introduction of elements foreign to the series, which makes them the most important part of the film.

But more can be done now than it could then, and Indiana Jones as a filmmaking experience never, ironically, was one for looking backward. When given that full freedom, Crystal Skull begins to take on a life of its own. The camera work during the rocket car sequences and the jungle escape is as fluid and confident as anything in Spielberg’s career. And it is fully modern Spielberg, diving back into the one-shot wonders he had experimented with in War of the Worlds just a few years previously.

Then it just as quickly retrenches, filling the screen with brown earth and green leaves, which neither hide the seams around the digital effects nor give real flowers to the out-of-the-world elements when they do arrive. These are not technicalities but speak to both the inherent conflict limiting Crystal Skull’s scope and the choices that result from that conflict.

It’s a reality that arrives both on a textual level – witness again an extended sequence of Jones and Co. finding and then breaking into an old tomb laced with booby traps, now raced through so quickly they barely make an impression — and a metatextual one — the last half of the film is primarily about Jones getting closure on the failed relationships of his life. Much as with Last Crusade, and even more explicitly than that film, the past Indiana is digging up is his own which is inherently limiting.

In some ways, it’s the natural evolution of a standard blockbuster. Indiana Jones’ initial attraction was a period adventure throwback popping up in the modern age. It worked because it broke perceived genre boundaries and created something new out of something old. But because it worked it set new boundaries, a template for itself. A template the series became locked into, limiting narrative choices to moving around within the frame rather than exploring relentlessly outwards. And once the character becomes literally within his own milieu, a creation of the past who only looks backward, he also becomes much less interesting.

As regressive as Crystal Skull can get, it benefits from being less so than its immediate predecessor and from genuinely attempting to bring new elements into the series. Right from the beginning, as Jones tussles with Russian saboteurs inside Area 51 and computers and jet engines roar, the film states that it will be less mystical and more technological than ever before.

This will be a science fiction story filled with aliens and spaceships and mind control, and Indiana Jones can freely pass back and forth between genres without being permanently attached to any one of them. Considering Lucas’ found art philosophy behind his pop culture behemoths this should not be at all surprising. It’s the logical progression of the kind of thinking which created the series in the first place, originally a hodgepodge of genres and tropes from the B moves of Lucas’ youth given an A movie sheen.

The passage of time means the films must eventually begin taking inspiration from newer and newer genres or risk becoming one of the very relics its main character searches for, sealed in a tomb behind vicious traps so that it can never be moved or changed.

None of this implies that Crystal Skull is an entirely modern experience, not least due to its period setting in the 1950s with equal parts Red Menace paranoia and Nelson family Eden. More importantly, it does continue to look back at previous Indiana Jones films for clues as to what worked before and what can be repeated.

Indiana is again saddled with an argumentative sidekick, Shia LeBeouf’s young Mutt in more of a Temple of Doom vein, and again faces a fascistic villain who is displayed as a darker version of Indiana and who shares many of his traits (right down to a signature weapon). Again, the villain is given a giant to serve as muscle and enforcer.

Forty years and four films later, Indiana Jones is still trying to discover what its core values are. The question remains unanswered apart from surface-level repetition. The feints at the way time is moving on and the need for accepting that and finding something new suggest some awareness of this problem, which is more than can be said for Last Crusade. But Crystal Skull never quite has the courage of its convictions. It suggests looking backward is safer and more fulfilling than looking forward, which is dangerous ground. The problem with being an archeologist is that eventually, there will be nothing left to dig up.

PREVIOUS: A LOOK BACK AT RAIDERS OF THE LOST ARK