Sketch comedy is hard. Really, all comedy is hard, but sketch comedy is really hard – getting long in and out in a (hopefully) short period without losing any part of the build or punchline. And while there is no reason old sketch comedy writers shouldn’t also be good comedy film writers, the reality is it’s a very different set of muscles.

Skill at one does not necessarily mean skill at the other. It’s even more difficult when satire is thrown into the mix, with the writer trying to develop a larger, serious point while keeping the jokes rolling.

The singular focus of a sketch becomes hard to sustain over a hundred minutes without becoming repetitive or getting lost within larger ideas.

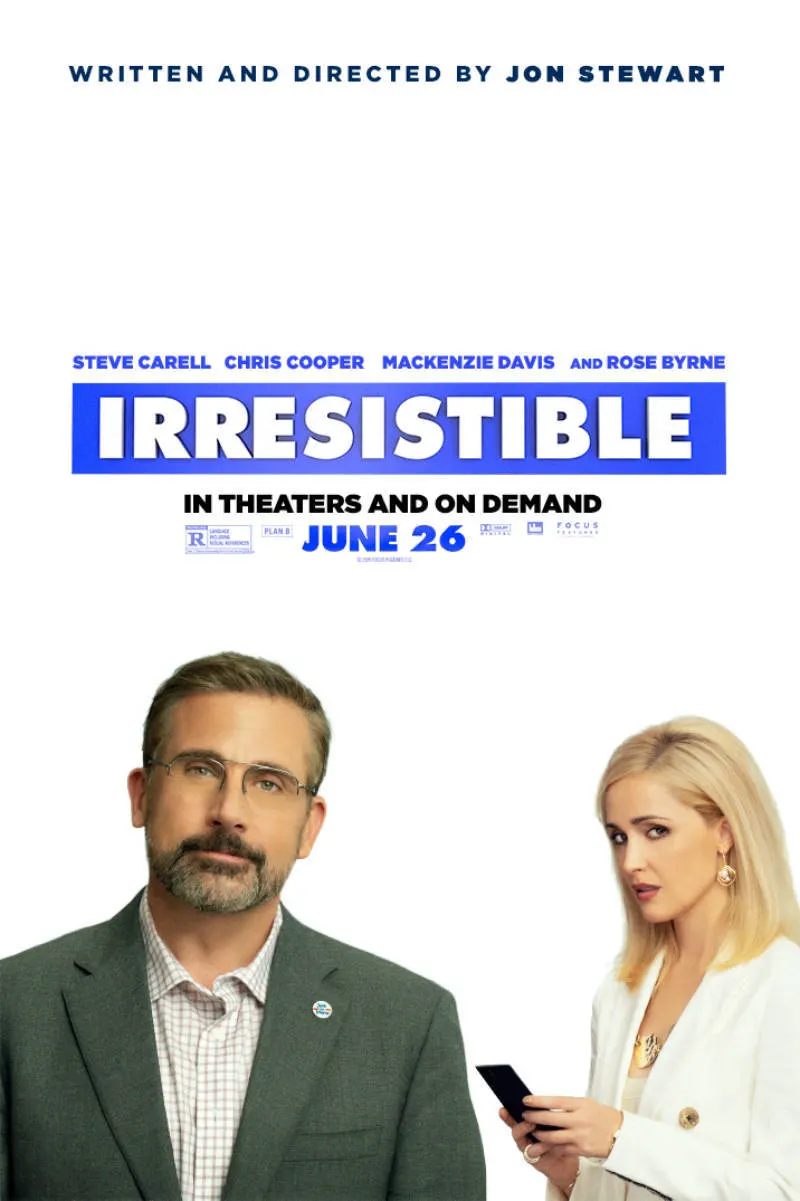

Jon Stewart is without question one of the best political satirists of this generation, but his first big swing at a feature film version of his patented blend of outrage is a terrific miss felled by an overreliance on worn-out tropes and such bottomless cynicism about the American political process it becomes difficult to even laugh at it.

Following the unexpected election of Donald Trump in 2016, long-time Democratic strategist Gary Zimmer (Steve Carrell) has been left without purpose or hope for his party’s place in American politics. Those hopes are flared back into life on the back of a viral video of a middle American farmer (living, as the captions say, in Heartland U.S.A.) and retired military officer (Chris Cooper) eloquently protesting the vilification of immigrants in his town.

With visions of a perfect rural American blue-collar Democratic template dancing in his head, Gary descends on Colonel Hastings and his town with all the money and bleeding edge political skills and money and how a better process and money it will take to make Hastings the first Democratic mayor in 40 years. When long-time rival Faith Brewster (Rose Byrne) arrives with the Republican machine in tow to make sure he doesn’t succeed, the experiment quickly escalates, with both sides willing to do whatever it takes to win.

There are a lot of noble intentions in Irresistible, maybe too many for it to be successful. Not just because the comedy is often overshadowed by the points it wants to make (and how that distorts the plot) but because they seem of such primal importance to writer-director Stewart (Rosewater) that the comedy doesn’t have to try as hard to still end up with something worthwhile. That’s tied to a desire to make use of and mock certain long-running comedy tropes, which gets far enough out of hand that, like the satire itself, the main purpose eventually gets lost. Irresistible spends so much time and effort reveling in tropes it loses the fact that it is no longer mocking or deconstructing these things but is actively engaging in them.

Not every political comedy has structured itself in terms of big town / small town with slick coastal elites guffawing at the simple naïveté of rural country life and looking like fools (and usually learning an important life lesson) in the process. But by god, a lot of them do. It may be the second most used plot in the genre, right after ‘idealistic newcomer slams into the grimy reality of practical politics and risks losing idealism which made him a good candidate, to begin with.’ Stewart makes use of every city mouse/country mouse cliché in the handbook, introducing Gary as the core of the jaded elite with his smart devices and his Tesla and private jet and his tragic attempt to ‘fit in’ to the town by switching to plaid and ordering a ‘Bud and a burger.’

Laugh at his perplexed awe at the town’s friendly greeting and quickly learning his name! Guffaw at his first introduction to homemade sweets and how much better it is than the mass-produced take-out he normally gets. Chortle at his ridiculous assumption that WiFi would be easily available when out in the middle of nowhere. There is some subtle shading that we ourselves are part of this joke by naively assuming these cliches are some form of reality and that Stewart really means them, but he spends so much time and effort on them that it’s hard to take that sort of chiding seriously.

Irresistible wants to have its cake and eat it, too, which is a strange sentiment for a film that is so firmly against the lifestyles of privileged wealth in the face of real need. You can’t easily make of Marie Antoinette while dressed and acting exactly like Marie Antoinette.

This is mostly also a sideshow to get at Stewart’s real point, which is far less about policy (despite being heavily ideological) and much more about the process. Stewart’s ultimate villain and ultimate target is money and, very specifically, the way it can pervert the political process even when in the ‘right’ hands. Just to make certain none of this is lost, he forces the film to place its primary thesis directly in Hastings’ mouth. We would all be better off, Stewart notes, if we took the money, we’re willing to throw at political campaigns (or any other cause or trinket that intrigues us) and just gave it directly to the communities the candidates are claiming they want to support. It’s not realistic, but the point is sound, and in Cooper’s hands, is as powerful as the rest of the film may wish it were.

And Cooper really is the film’s secret weapon and the main reason to watch it. He very carefully treads a line between ‘aw-shucks’ naiveté and fundamental wisdom needed to be able to point out evil while not being seemingly corrupted by it. In that sense, he is, very intentionally, a creation – the kind of person who can’t possibly exist in real life but in whom we can place our most unrealistic ideals. Which is, not coincidentally, the type of role Cooper has become very good at playing. He’s earnest without seeming silly or slow and, most importantly, without being trampled by any of Carrell’s silliness. And that’s no small thing, especially once Rose Byrne’s Faith arrives and begins to bring out Gary’s worst impulses.

Unfortunately, Cooper is hopelessly out of place in the film as an idealistic island in a sea of cynicism. Real jokes need teeth, and cynics bite harder than any other type of satire, but the risk always becomes so bleak and acidic that the laughter no longer comes. Irresistible can’t even claim to be a black comedy and invite the audience to laugh at its awfulness because it’s trying to offer a message of urgent change even when every element of its body language suggests positive change is a figment of our imagination. It would all probably be easier to take if the cynicism weren’t so bottomless.

It’s one thing for everyone to be the potential butt of a joke; it’s another for the jokes to always be about what buffoons lack in even simple dignity its targets. No one is safe because, in the film’s eyes, no one is clean.

When this gets terribly out of hand, Stewart does revert to some ludicrous bits, which would be easily at home in a Daily Show sketch (and in some cases are just recreations of Daily sketches). But silliness (and it can, occasionally, be tremendously silly) is not the antidote to cynicism by itself. Worse, swinging wildly from bleak satire to outrageous set pieces to blue sky optimism and back again is jarring without offering enough laughs to be worthwhile.

Irresistible wants to leave us with some thoughts about the future and maybe a few good punchlines, but it doesn’t do much of either. It’s not ridiculous enough to be good satire, not charming enough to be good comedy and not serious enough to be good drama. It’s just not really anything.

Irresistible Review Score: 5/10

Irresistible will be available On Demand starting June 26th for a 48-hour rental period for $19.99.

Joshua Starnes has been writing about film and the entertainment industry since 2004 and served as the President of the Houston Film Critics Society from 2012 to 2019. In 2015, he became a co-owner/publisher of Red 5 Comics and, in 2018, wrote the series “Kulipari: Dreamwalker” for Netflix. In between, he continues his lifelong quest to find THE perfect tomato soup and grilled cheese sandwich combination.