Somewhere, on the side of a mountain in the Appalachians, a family is gathering for its annual celebration. Somewhere, a family is falling apart. Somewhere, the classic reactions and responses to unconscionable betrayal are turned on their heads.

Somewhere, people act out their lives in a fashion both impossible to identify with and unmistakably human. South Mountain is both a hauntingly unique story of heartbreak and heartmending and a classic staple of the character drama form.

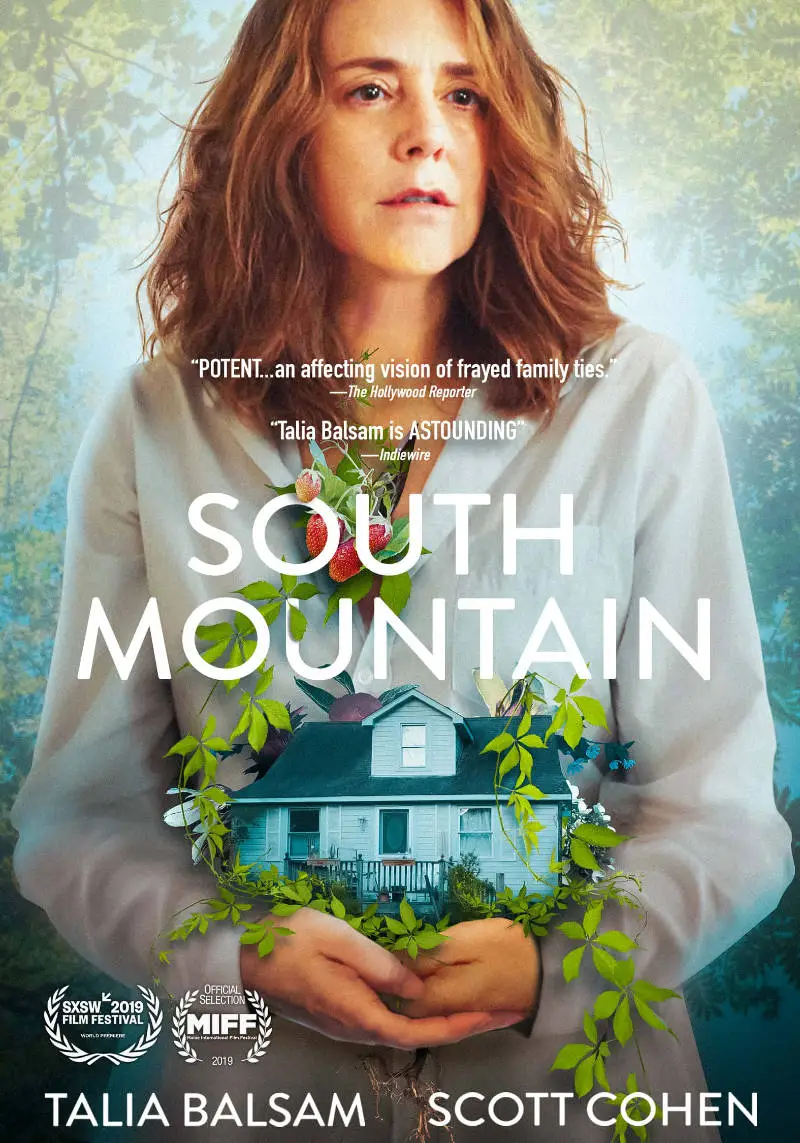

The gathering is that of Lila (Talia Balsam) and Edgar (Scott Cohen), a middle-aged married couple celebrating their latest Fourth of July with their teenage children and old friends. One of them, however, knows a life-breaking secret that will slowly but surely come spilling out over the next month and change.

Edgar has fathered a child with another woman, and though Lila initially does not want to embrace the standard reaction to such news, it soon becomes clearly inevitable what must be done. As slowly as news of Edgar’s actions spilled out, so do the reactions filled with denial and acceptance and wrapped around visits from friends and family stuck within their own preoccupations.

South Mountain is a low-budget, character-oriented independent film. That isn’t a pejorative or a warning any more than stating that a film is a big-budget action movie or a Blumhouse horror project. It’s simply a spoken announcement of the type of film involved, invoking an unspoken aside that certain cliché of the genre will be involved. It’s worth repeating that cliché also aren’t de facto negatives.

It’s just that familiarity brings both contempt and comfort, and it’s a constant reminder that we’ve been this way before. Not that being unique and different is a perfect antidote to those problems, but it’s also not an issue South Mountain spends a lot of time debating. To paraphrase Dune, “the forms must be obeyed.” Well, maybe not must, but they certainly will be.

There are long, silent, all-encompassing shots of nature with human beings occasionally wandering through. There are long, underplayed conversations about past and present emotions, with plot details left to be filled in behind the scenes. There is a direct, intentional attempt to avoid obvious dramatic fireworks, focusing instead on the slow, long-term reactions to such changes. In fact, that’s pretty much all South Mountain is: a reaction. A reaction to hurt, a reaction to pain, a reaction to history, a reaction to happiness, a reaction to life.

A lot of that is dependent on the skill of the actors, as the minimalism of the story and the visuals leaves us with only the people to hang on to. And that is a responsibility mostly on Balsam’s shoulders as Cohen (and to an extent most of the characters) floats in and out of Lila’s life, just enough to bring up memories of love and pain and let us see how plainly they appear on Balsam’s face. And her face is just about the only place we’ll ever get to see that deeper truth writer/director Hilary Brougher seems to be going for because everything else is just so intentionally low-core.

It’s not mumblecore; no one speaks near enough for that (or for it to be accused of resembling a play, though it shares some elements with theatrical drama), but it’s similarly low-key to the degree the casual viewer may wonder just how much any of this matters to the people living through it.

Not everything needs wild plot gyrations, and South Mountain would feel false with them. But it’s impossible to erase the feeling that something has happened and we missed it. There was a moment where the world changed, and we were looking the other way. What’s left is regret or acceptance. Or both. Brougher wants us to see why both are not so much needed as inevitable, with much to recommend and condemn them.

And she does it skillfully, never yanking the bandage off or going for the visceral thrill. Even the most melodramatic moments — the reveal of Edgar’s infidelity — are approached from the side, growing in scope until they are impossible to ignore. Similar to the way we slowly learn that a phone call Edgar is having is with the woman giving birth to his child, we learn bits and bits and bits about Edgar and Lila’s long history with its ups and downs, creating more and more context for Lila’s reactions and her long delay of accepting how life has changed.

It works better in theory than it does in practice – it truly does need a few more layers of dialogue and just speech to open the character’s inner lives to invest an audience fully in their lives.

But once the forms are observed and seen through, there is real meat on South Mountain’s bones. Brougher’s touch is so delicate it is almost invisible, which denies Mountain the forward momentum it desperately needs. But just sit back and let it wash over you like a cleansing rain, and its depths will be revealed in the aftermath.

South Mountain Review Score: 7/10

Written and directed by Hilary Brougher, Breaking Glass Pictures‘ South Mountain stars Talia Balsam as Lila, Scott Cohen as Edgar, Andrus Nichols as Gigi, Michael Oberholtzer as Jonah, Macaulee Cassaday as Sam, Midori Francis as Emme, Naian González as Dara, Isis Masoud as Gemma, Guthrie Mass as Jake, and Violet Rea as Charlotte.

Joshua Starnes has been writing about film and the entertainment industry since 2004 and served as the President of the Houston Film Critics Society from 2012 to 2019. In 2015, he became a co-owner/publisher of Red 5 Comics and, in 2018, wrote the series “Kulipari: Dreamwalker” for Netflix. In between, he continues his lifelong quest to find THE perfect tomato soup and grilled cheese sandwich combination.