The biopic is a surprisingly elastic storytelling tool. In theory, it exists to present an overview of a life. But what is life? It can be tragic, uplifting, or enthralling, and often, all of those together within the same span of years.

By the same token, the biopic can be a tragedy, a warning, a eulogy, or a hagiography, depending on the point of view of the person telling it. Above all, though, it is a story.

The story of Fred Hampton’s (Daniel Kaluuya) life and death is the same question the filmmakers creating his biography are wrestling with: what is a life? And what is it worth? For Hampton, the answer is simple – raising his community out of the pain and poverty of systemic racism by any means necessary.

A powerful orator and intellectual, Hampton is fueled by the indignation felt by everyone in his community but also sees the way through it and the challenge to the ruling systems of the United States that path will take. He also sees the danger of violence and fighting even as he embraces the need for it and the difficulties he and his people will need to embrace in order to find true freedom. Seeing those paths and following them turn out to be two different things, with his personal and political desires increasingly at war with one another and time quickly running out.

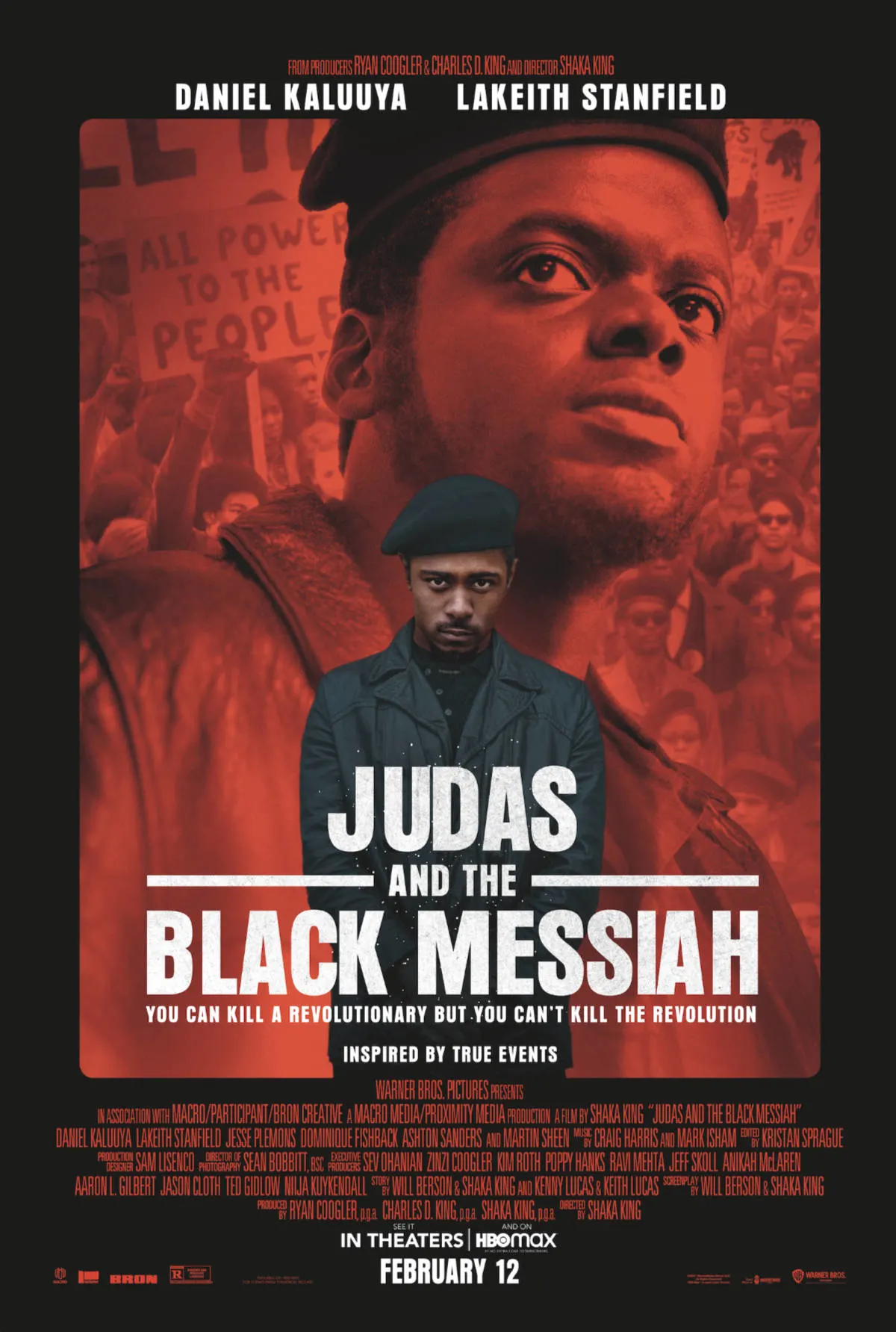

If Fred Hampton had a laser focus on the meaning of his life, his biography would not be so lucky. Judas and the Black Messiah is a riveting, infuriating look at part of Hampton’s life, which also tries to contain all the context surrounding his life and death with the Black Panthers. That is a giant remit, and co-writer/director Shaka King never quite grasps ahold of it.

Considering the width and breadth of what Hampton was trying to accomplish and the distance in time since he lived, there is a lot of logic in attempting to create a full context of that specific moment of his life. It’s not just for dialectic reasons (though there is certainly plenty of that) but to replicate the emotional context of his death at the hands of the Chicago police.

It’s commendable, but the reality is that a biopic can contain a lot, but it can’t contain everything. Perhaps if the story were singularly focused on Hampton, it would have worked better, but King instead focuses on FBI infiltrator William O’Neal (Lakeith Stanfield) as the point-of-view character for entrance into the world of the Black Panthers.

A low-level car thief looking at significant prison time for impersonating FBI agents as part of his grift, O’Neal is instead recruited to join the Black Panthers and report on Hampton’s movements and activities, even as he becomes more and more receptive to Hampton’s message.

These types of removed point-of-view characters tend to show up when dealing with difficult central figures that the filmmaker can’t or doesn’t want to embrace fully. Hampton is fully defined and embraced as a difficult person and easily the most robust personality in the film, while O’Neal, the theoretically accessible character, is left as an undefined cipher who spends most of his time looking over what Hampton has wrought.

What does he think of this savior he has hooked up with and the idea of betraying him? What does he really want besides getting away from the FBI? We never really find out, despite spending more time with him than any other person in the film.

On top of that strained character relationship are thrown all the other members of the Illinois chapter of the Black Panther Party, such as the beleaguered mother of Hampton’s child, O’Neal’s FBI handler, and even J. Edgar Hoover (Martin Sheen). Trying to tie all these disparate characters and motivations together into a straightforward story is difficult and results in a fractured film that loses focus whenever Hampton isn’t around.

This could be a result of two different scripts being melded together. There is a story to be told about the Judas and a story about the Messiah, but trying to do both at the same time is a bridge too far.

The performances both help and point out this issue. Kaluuya is magnetic, as Hampton and Stanfield do a lot with an ultimately empty character who is crying out for more definition. What he does do is provide opportunities for Kaluuya or Jesse Plemmons (as his handler) and even for Dominique Fishback to create their roles but at the cost of being a fully realized character.

If anyone is the real find in Judas and the Black Messiah, it is Fishback as the one person who can call Hampton out on his own selfishness (of which he has much, even if it is well founded).

Director Shaka King, working on his first big studio film, makes many of the individual scenes sing, creating a rising tide of dread, frustration, and hopefulness. But it’s a tide that crests repeatedly.

Rather than building and building to the fateful assault on Hampton in Chicago, it rises and falls and rises and falls, dashing momentum. That may be truer to life, but it’s not a great way to tell a story. And we’re in the realm of Judas and Messiah. We are definitely in the realm of stories.

JUDAS AND THE BLACK MESSIAH REVIEW SCORE: 7/10

Judas and the Black Messiah is now playing in select theaters and available to stream on Max.

Joshua Starnes has been writing about film and the entertainment industry since 2004 and served as the President of the Houston Film Critics Society from 2012 to 2019. In 2015, he became a co-owner/publisher of Red 5 Comics and, in 2018, wrote the series “Kulipari: Dreamwalker” for Netflix. In between, he continues his lifelong quest to find THE perfect tomato soup and grilled cheese sandwich combination.