With this Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade feature, we’re taking a look back at Lucasfilm’s other giant franchise and the ways it shaped the modern blockbuster. Stay tuned for all the latest Indiana Jones 5 news here.

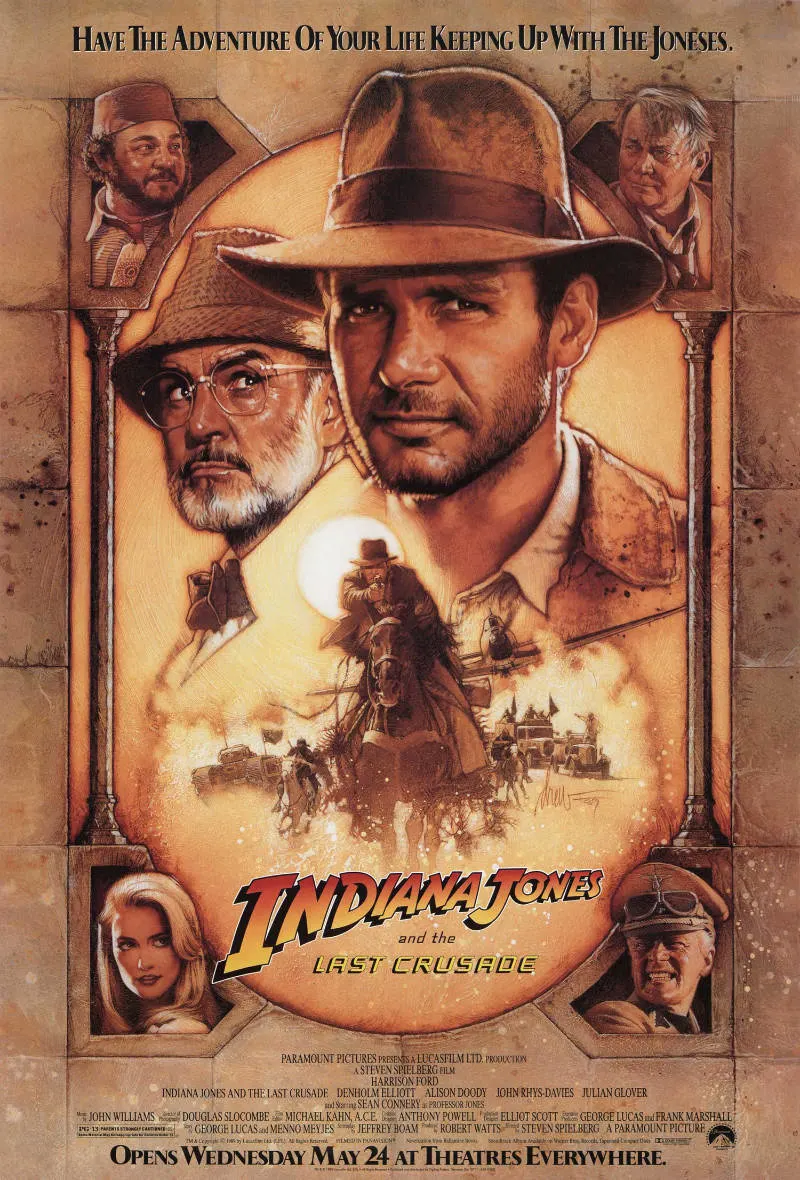

INDIANA JONES AND THE LAST CRUSADE

Like any series with a spectacular start, most of the analyses of all of the films that followed have focused on how they came up short. Why they weren’t as good as the original and what the series needs. Certainly, every Indiana Jones film has faced that to one degree or another: Temple of Doom was too dark, Crystal Skull was too campy, etc.

A lot of series get by with the repetition of major elements from film to film to film. To an extent, this is the definition of a series. Core elements are repeated multiple times (because, generally speaking, they work). But it requires an understanding and agreement on what that ‘core element’ is.

By comparison, Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade (buy at Amazon) has been spared much of that, with the conventional wisdom being that it was a return to form after the weirdness of the second film. That was clearly intentional on the part of everyone involved in making it and one of the two big reasons why Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade is the weakest film in the series.

The Last Crusade’s answer to that question is everything Raiders of the Lost Ark had.

That’s not a bad answer (even if it does skip one entire movie’s worth of material about what the series could be), but it is a very regressive one. More to the point, it is very confusing and unhelpful. Generally a series gets focused down to its core character and the events which affect them, but whose details can change from outing to outing.

The strength of the core character’s personality – and the writer’s understanding of those strengths – feeds the series from story to story, even when the plots get dicey. By grabbing up and repeating everything, the filmmakers at least implicitly state that they don’t really know who the character is or why the first film works.

By holding on to everything, the message is sent that everything is required for the films to work, and no element can be removed without the whole thing coming down like a Jenga tower. It’s not enough to have Indiana Jones going on adventures, he must also be racing against the Nazis, preferably in a desert setting at least once.

And he must do nothing else as if the defeat of the Nazis also causes Indiana Jones to disappear in a puff of smoke like one of his mystical treasures. [Or perhaps head to South America to keep the few survivors from cloning Hitler and rebuilding their army].

That’s not to say nothing new has been added.

It’s the first time that Steven Spielberg’s particular ideas make themselves fully felt in an Indiana Jones film, specifically a discordant father-child relationship that casts a pall over the child’s adult years and prevents him from living his fullest life until it is dealt with. Every Spielberg critic or analysis ever — not to mention Spielberg himself — has commented on how fixed Spielberg is on this particular type of conflict and how often it appears in his work.

Not that there’s anything wrong with that, any more than there is with the recurrence of Hitchcock’s need to control his actresses in his own film. It’s an intrinsic part of the Spielberg experience and one which notably fills his ‘popular’ work (E.T., Close Encounters of the Third Kind, Indiana Jones, The Lost World: Jurassic Park) but is intermittent in his more ‘serious’ work.

Unfortunately, it swallows Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade whole.

Even a surface-level view of Spielberg’s work makes clear how important themes of a broken family and an absent father are to him, either attracting him to a story or being inserted into one. Many words can and have been written about Spielberg’s particular interest in these themes, which stem from his past history and affect what he makes. [This reaches its natural apotheosis in Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull].

As Indiana Jones the series ages, these interests naturally insert themselves into it, turning the series focus from ‘where is it going?’ to ‘where did it come from?’ It starts with an extended flashback into Indiana’s youth (explaining vital mysteries like ‘where did he get his hat and dress sense’) and continues to drop small hints throughout its runtime about what his youth was like and what his given name is.

Granted, it does give us Sean Connery’s Henry Jones, Sr., who is one of the best characters in the series.

And Sean Connery is the operative phrase in that description. Henry Jones, Sr., on the surface, is the opposite of Indiana, both making his characteristics easy to generalize and juxtaposing him against Indiana’s myriad adversaries who tend to be much more like Indiana than his father is. It says a lot about Indiana and his nature as a reaction against his father, though it’s never focused on to any extent again outside of Last Crusade.

But it also makes Henry a potential caricature because he is defined by someone else and not by himself. Indiana is outgoing and rugged, so Henry is bespectacled and bookish. Indiana is warm (at least to his closest associates), so Henry is distant and demanding. Even their dress sense is reversed — leather versus tweed, bullwhip versus umbrella — to make sure at any moment the differences between them are clearly understood at the most basic levels.

They are a comedy of opposites. To some extents this is a necessity of blockbuster life, the goal is for the greatest number of people to understand and follow along which by necessity means heaping helpings of reduction and repetition. The side effect of that is it nearly turns Henry into a cartoon.

But in Connery’s hands, it’s a cartoon that comes to life. He invests Henry with a difficult mixture of heady mixture and childish petulance – what he thinks is important is important, and everything else is besides the fact. Indiana’s decision to leave home with little later contact was an active attempt to disrupt Henry’s work, and his insistence on not getting shot by Nazis is almost as bad.

Connery juggles these competing instincts gleefully, managing what film acting most requires but seldom offers – the suggestion of a richer inner life than the plot or dialogue fully conveys.

Most importantly, it adds new layers and dimensions to Indiana Jones himself. Not just by adding more details of his youth and background and REAL NAME (which ultimately are more of a sideshow than actively important) but by offering something new for the character and its actor to bounce off. Temple of Doom showed the pitfalls of making most of Indiana’s screen relationships romantic and the limitations of putting on screen with youngsters as well.

Focusing on the past ironically allowed Indiana to do something new – talk about himself and why he is the way he is – and created a new on-screen dynamic the series had never attempted before. Alison Doody’s Elsa is a sad after thought, literally existing because someone thought there had to be some sort of love interest but ultimately lost in the wake of the only relationship which really matters in the film.

That would all probably work if the Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade as a whole weren’t just so reductive but so regressive.

Somehow, Indiana Jones has forgotten all of the lessons of its forebears, both in film and character. It’s one thing to make each film similar, it’s another to give them amnesia. He still chases heedlessly after treasure (even if his more mercenary side is less in control) even as it has that nature has gotten him into trouble constantly in the past.

It’s one of the few traits he shares directly with Henry Jones, Sr., which would be more interesting if it wasn’t the key part of his personality that had been so well documented already. It’s as if not only the surface elements but also the original character traits were determined to be key points of the series that could never be changed, only repeated, allowing for no change or growth. Everything that worked so well that Last Crusade eventually became exactly what the series didn’t need: a template.

The deep dive into Indiana’s youth and family is immediately interesting and opens up new avenues for him as character, but they soon overpowered everything around him to become the only stories to be told about him. Who was his father or mother? Did he have children? How did they adapt to his life of adventure? Was he an emotionally absent family member the way his father (and some of the filmmakers’ parents) were?

And it all stems from the impact Connery made here, converging with the classic storytelling impulse of ‘if it worked once, let’s do it again.’ As good as Connery is, it’s impossible not to feel that the whole series would have been better off if Henry Jones, Sr. had never been introduced.

And everyone involved seems to feel it with the first ever missteps in execution in a series which formerly made that a core part of its appeal. The bold experimentation in the palette as an indicator of tone is an early sacrifice to the need to return to the desert chases of Raiders, although the early attempts at a haunted house story are spectacularly moody.

The score is lively as well, but with a few exceptions, the inventiveness behind the set pieces is severely diminished in favor of repeating old favorites – nothing in Last Crusade reaches the level of the Raiders or Temple of Doom’s best action beats. Worse, some of the effects work is actively shabby, with visible matte lines and strange perspective issues marring suspension of disbelief even as the technicians took some of the first steps into the realm of digital effects.

There’s a certain level of nitpicking at that point – most of Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade’s craftsmanship is impeccable. But none of it is inspired. The focus is all on the past. For a series about an archeologist, it’s amazing that it took so long for a film to begin rooting around in Indiana’s own past, but that ends up costing more than it earns as Jones never looks forward to the future again. Not even when escaping from an atomic bomb.

On the other hand, we may have missed out on one of the single best episodes of The Young Indiana Jones Chronicles, so maybe it was all worth it after all.

NEXT: A LOOK BACK AT INDIANA JONES AND THE KINGDOM OF THE CRYSTAL SKULL

Joshua Starnes has been writing about film and the entertainment industry since 2004 and served as the President of the Houston Film Critics Society from 2012 to 2019. In 2015, he became a co-owner/publisher of Red 5 Comics and, in 2018, wrote the series “Kulipari: Dreamwalker” for Netflix. In between, he continues his lifelong quest to find THE perfect tomato soup and grilled cheese sandwich combination.