If Hollywood is our guide, great natural disasters have no greater purpose than to focus on a long-standing interpersonal conflict (usually a married couple) and give the participants one big chance to clear it up. Mother Nature isn’t just the personification of our system of physical laws making sure the world works the way it needs to.

She’s also the ultimate marriage counselor, ginning up such unbelievable catastrophes that we ordinary people are finally forced to stop gazing at our navels and focus on what’s really important.

From Deep Impact to Twister to 2012, the modern take on the disaster film is a relationship drama writ large. It’s a tradition Greenland fits snuggly into.

The disaster in question is a rain of deadly meteoroids preceding one final giant collision expected to wreak havoc on a level similar to the extinction of the dinosaurs. Rather than focus on the officials dealing with such an event, Greenland focuses on the reactions of ordinary people as they seek some sort of safety from a sky suddenly lighting on fire.

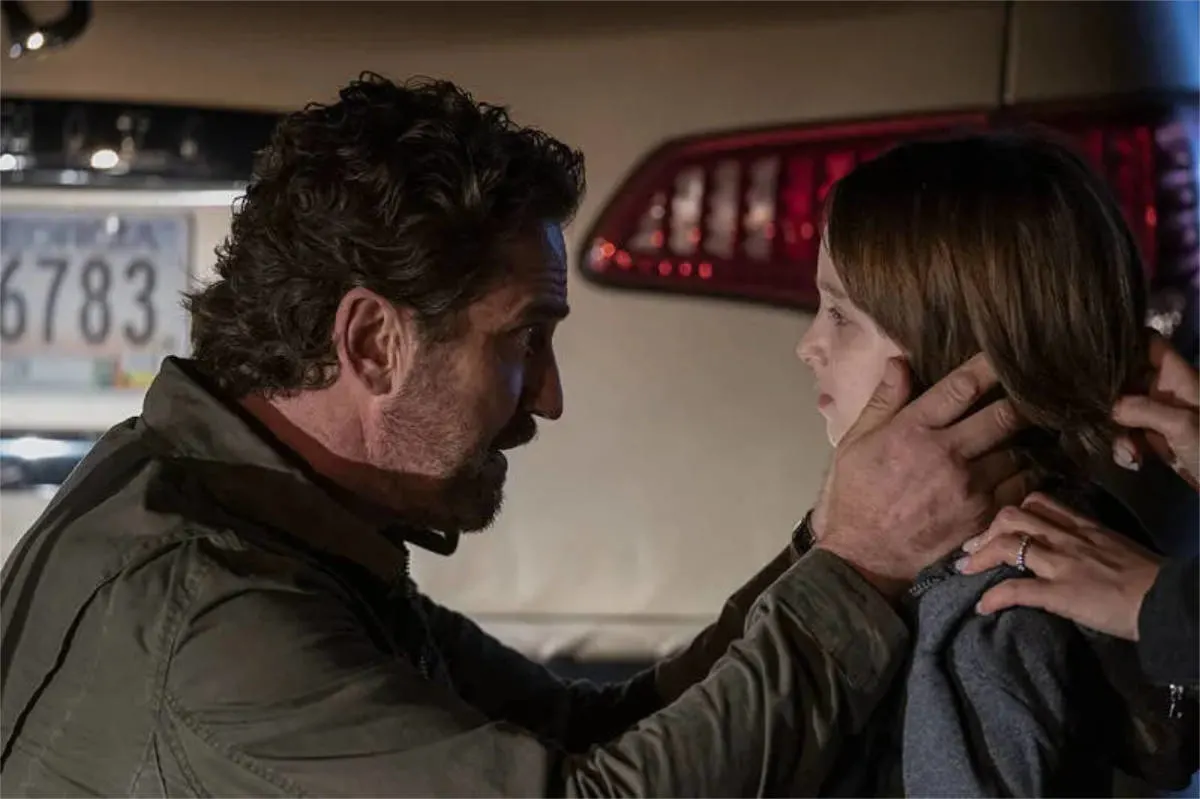

Unlike most of the populace, John Garrity (Gerard Butler) and his family have been selected to shelter in the government’s secret bunkers deep within Greenland… if he can get them there. Fighting desperate people, the fall of society, and his slowly unraveling marriage, John attempts to get his family there, hoping the secret shelter actually exists.

This is not the only way to do a disaster film. Once upon a time, they were more procedural, less melodramatic with a focus on the experts and officials trying to negotiate the world’s largest earthquake or (more than once) dealing with a falling meteor from space.

Sure there would be some normal guy in a subplot giving us a man-on-the-street view of the unfolding drama, adding some relatable stakes for the president or scientist or whomever to save (sometimes unknowingly).

Slowly, inexorably, like a killer iceberg slamming into the continent, that man on the street took over the plot, sending the expert off to a closet to fiddle with his slide rule. It’s as if the culture war against intellectuals escaped from television and invaded movie theater screens as well.

The problem with this change is that it highlights why the original, most intuitive way to tell these stories was to deal with the people in the middle of them, coming up with solutions if possible and making the most difficult choices. The drama in such elements is obvious. The drama in the man-on-the-street character is less so beyond the dread of not knowing what is happening, which can only stretch so far.

This gap most often places a marriage or similar relationship in jeopardy, which must be mended before everyone dies. It was a decent idea once, but after many identical iterations, it has become difficult to gin up the same level of enthusiasm for the latest version of the disaster story.

Butler and Morena Baccarin try their best to keep you from noticing. Director Ric Roman Waugh and Butler did interesting work in Angel Has Fallen to move macho secret service agent Mike Bannister away from his bullet-chewing, lightning-throwing conception and engage with the mental and emotional toil his work must take on him.

They go even further with Greenland, allowing Butler out of the constraints of action-hero manliness and letting him bask in the difficulties of fighting a stranger for the last seat on a bus or suddenly feeling the wait of a meteor attack land during a quiet moment.

And Greenland has a lot of quiet moments. Whether out of artistic or budgetary reasons, most of the meteor strikes and disaster scenes happen off camera, usually just out of the corner of the eye with a spreading fire cloud constantly in the cameras’ peripheral vision as a constant reminder of what’s just beyond the horizon.

That time is instead given over primarily to Butler and Baccarin as they deal with each other and the constant threat of death chasing them. Both of them rise up to the occasion.

Somewhere along the line, however, someone realized how difficult it would be to sustain an entire film this way. It tends to get very obvious when entering the third scene of people driving a car and talking in a row… a lot of Greenland happens in the dark or in a car or in a dark car.

[Steven Knight maybe could have made something out of this, but it’s more of a question for Waugh]. To keep things happening, many extremely contrived obstacles are shoved in John and their family’s way to artificially separate them to up the tension before more driving is called for.

It’s not bad, but it’s not great either. The natural disaster as relationship drama mold has been pushed about as far as possible, and if Greenland proves anything, it’s that moving the leaders and experts off-screen makes it difficult to sustain the world-ending drama.

Unexpectedly more dramatic than action-packed with strong, subtle performances from its leads, Greenland doesn’t offer enough new to really sustain its concept, but there are worse ways to spend a few hours.

Greenland Review Score: 6.5/10

Greenland is now available to rent in HD for 48 hours. The film previously opened in international theaters.

Joshua Starnes has been writing about film and the entertainment industry since 2004 and served as the President of the Houston Film Critics Society from 2012 to 2019. In 2015, he became a co-owner/publisher of Red 5 Comics and, in 2018, wrote the series “Kulipari: Dreamwalker” for Netflix. In between, he continues his lifelong quest to find THE perfect tomato soup and grilled cheese sandwich combination.